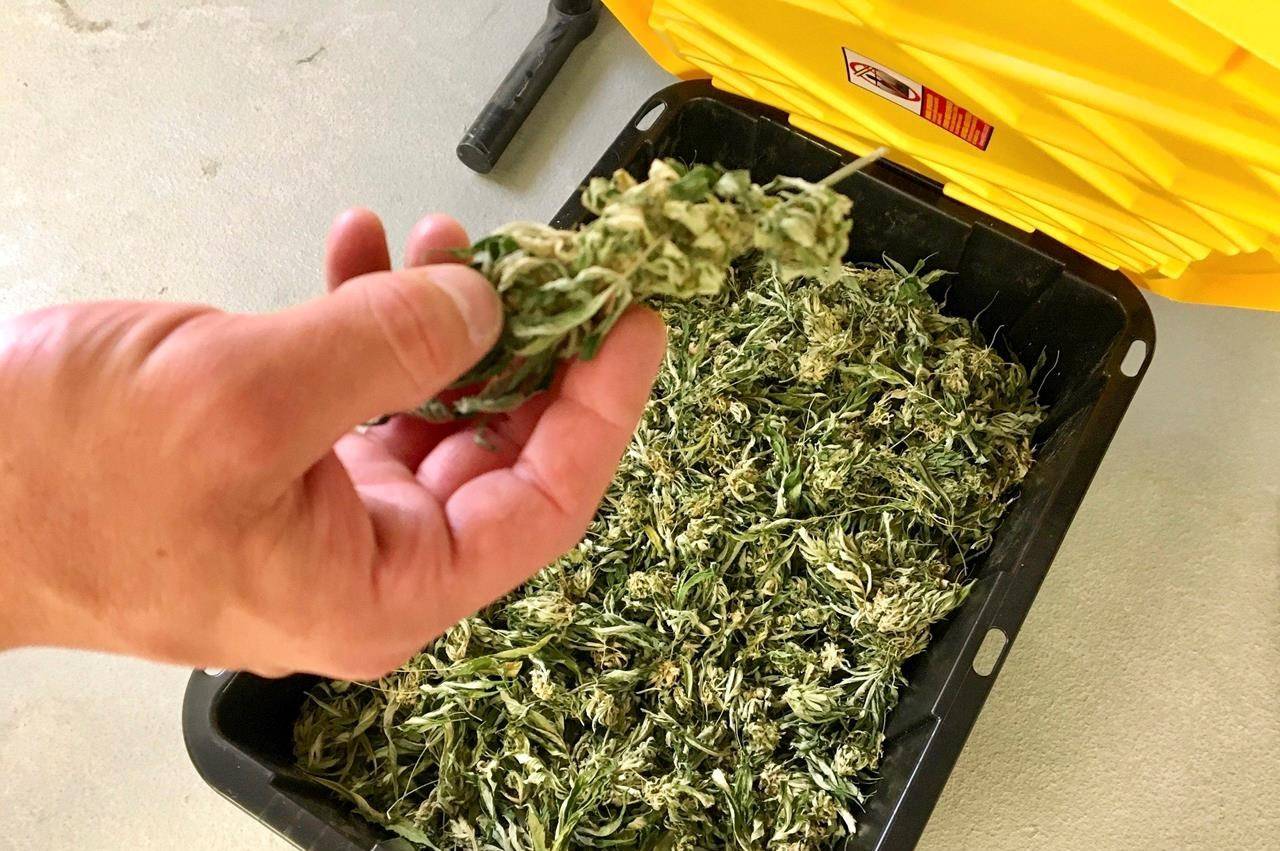

Pain left from oil-field work defeated traditional pain pills and dominated William Adams’ life — until he tried medical marijuana. But even as he began venturing outside his home for the first time in years, Adams discovered he couldn’t afford the cost.

Medical cannabis typically isn’t covered by insurance or Medicaid because it remains federally illegal. The group that led the push to legalize it in conservative Utah says that has kept it unreachable for many patients who need it.

The Utah Patients Coalition on Tuesday joined a small but growing list of programs around the U.S. aimed at helping low-income patients access the drug. The project is among the first to offer ongoing subsidies statewide.

“I thought that we had relieved a lot of suffering, and I can’t deny that we have,” said Desiree Hennessy, executive director of Utah Patients Coalition. “But then the phone calls have changed from ‘Hey I need help, I need cannabis’… to ‘I can’t afford to go to the doctor.’ ”

The coalition has partnered with cannabis pharmacies across the state that will offer discounted medications to patients approved for the subsidy.

Similar programs include one in Berkeley, California, for patients making less than $32,000 a year. They can access medical cannabis for free at local medical dispensaries through a city ordinance. States like Florida and Oregon offer reduced prices for state medical cannabis cards.

In New Mexico, a longstanding proposal to create a “low-income medical patient subsidy fund” to underwrite medical marijuana purchases failed this year as the state legalized recreational pot during a special session. New Mexico soon will waive taxes that currently apply to medical marijuana sales and the new cannabis excise tax for medical patients — a discount of nearly 20% in most cases.

The lead House sponsor of the successful legalization bill there has vowed to reboot social and economic justice provisions that were stripped from the legislation.

Emily Kaltenbach, a senior director at the Drug Policy Alliance, said subsidy programs like the one in Utah are critical for low-income patients who have limited options to be able to afford their medicine. One challenge the Utah program may face is raising enough money to keep it going long term, she said.

“We see patients who not only can’t afford their medicine but they also can’t afford doctor’s visits,” said Kaltenbach, who is based in New Mexico. “Many of them are uninsured and so the cost of the visit to get certified to be a patient and then the cost of medicine can have a huge impact.”

Dragonfly Wellness, Utah’s first marijuana pharmacy, announced Tuesday that it would be donating $130,000 to the subsidy program, which will be entirely funded by donations.

Hennessey had tears in her eyes as she described the impact that money will have on patients’ lives. She said it will likely cover the cost of subsidizing medication for the more than 400 terminal patients who have applied for the program.

“I have hope that we are actually going to fill the need,” she said.

Utah became the 33rd state to legalize medical marijuana after voters passed a ballot initiative in November 2018, though the program has especially tight controls under a compromise involving The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, whose positions carry outsized sway in its home state.

After contacting his cannabis pharmacy about his financial concerns, Adams, 38, became the first person to pilot the coalition’s subsidy program in January. Now his pain has subsided enough that he can go out and enjoy the parts of life he had been missing out on — spending time with his family, fishing and even riding his motorcycle.

“I’m a whole different person with a whole better life than I was six months ago,” Adams said. “Being able to manage pain correctly, it just changes everything in every way.”

Associated Press writer Morgan Lee in Santa Fe, New Mexico, contributed to this story.

Sophia Eppolito, The Associated Press