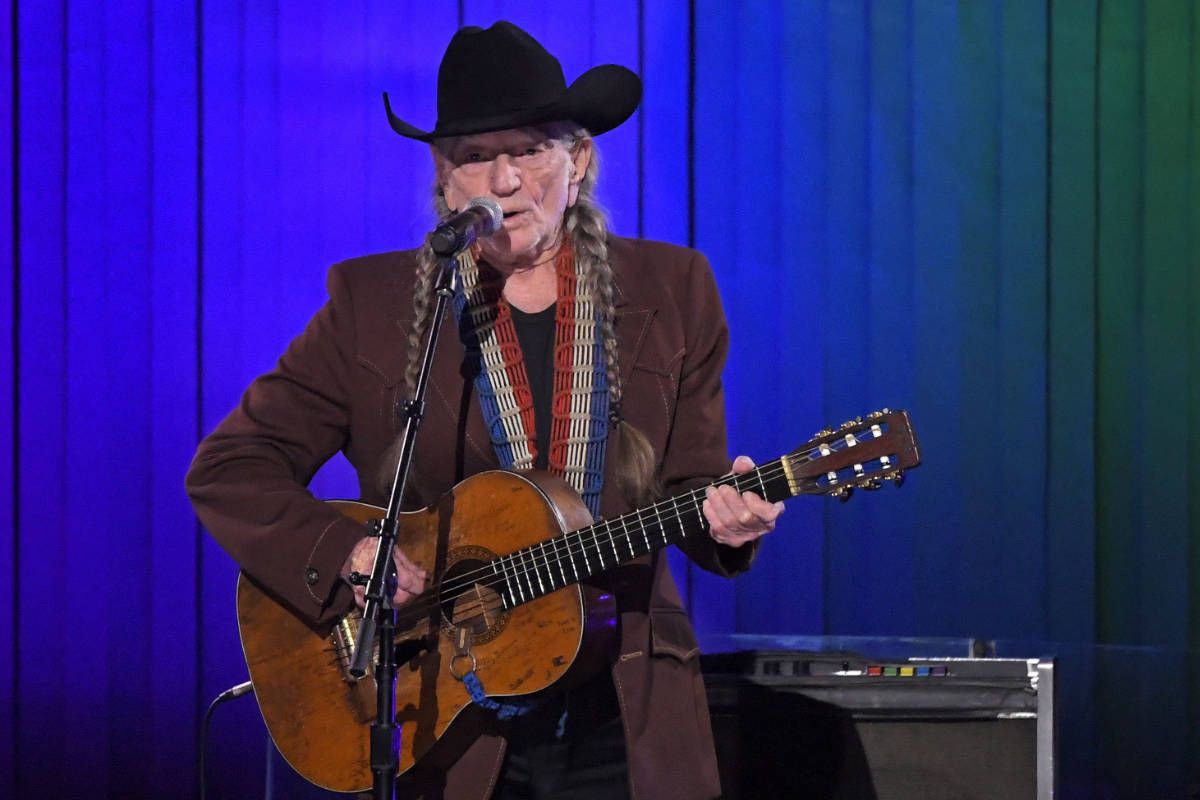

Near the beginning of “Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President,” the new documentary that explores the 39th president’s connection to the music community during his four-year term, President Carter offers a revelation involving one of his children, country singer Willie Nelson and what Nelson once described as “a big fat Austin torpedo.”

Asked about Nelson’s account of smoking cannabis on the roof of the White House at the tail end of Carter’s term in 1980, the former president lets out a chuckle.

Nelson, Carter explains in the film, “says that his companion that shared the pot with him was one of the servants at the White House. That is not exactly true. It actually was one of my sons.”

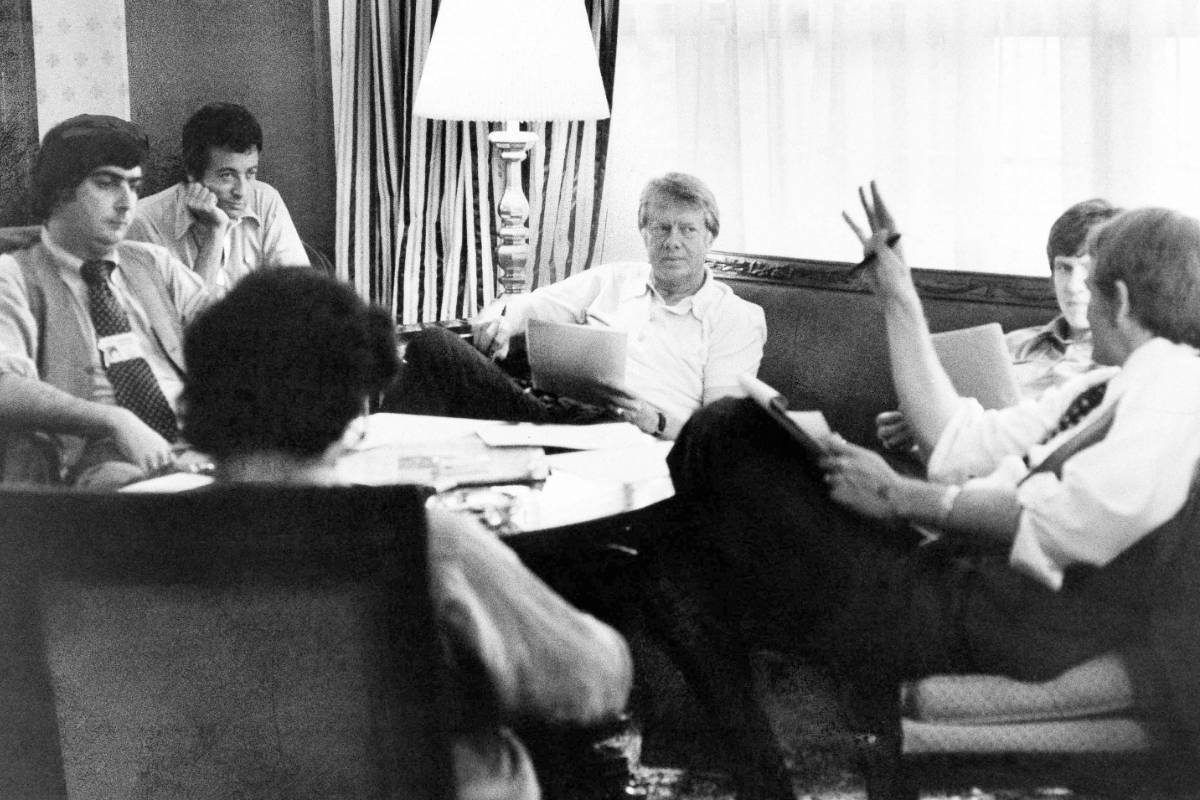

It’s a brief exchange, but the coy interaction sets the tone for this affectionate, revelatory film about the ways in which a Georgia peanut farmer, on a mission in 1976 to upend American politics, tapped a kind of political action committee of artists, stoned or otherwise, to make his long-shot run at the presidency. Once victorious, Carter opened his doors to musicians, their art and at least one illicit joint.

Directed by Mary Wharton and produced by Chris Farrell, “Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President” celebrated its theatrical release on Tuesday, part of an extended rollout that will see it move from theater to on-demand in October to, ultimately, CNN at the beginning of 2021.

At one point in the film, Carter sits next to a turntable with Bob Dylan’s “Bringin’ It All Back Home’” cued up and says matter-of-factly, “The Allman Bros. helped put me in the White House by raising money when I didn’t have any money.”

Across Carter’s term, artists including Nelson, Charles Mingus, Loretta Lynn, Bob Dylan, Sarah Vaughan, Cecil Taylor, Linda Ronstadt (who had campaigned against Carter with her then-boyfriend Jerry Brown), the Staple Singers, Cher (and her then-boyfriend, Gregg Allman) and Tom T. Hall either visited or performed at the White House. Crosby, Stills and Nash once dropped by the place unannounced. Carter made time for them.

The musicians’ very presence was a grand shift. Inheriting a Vietnam War-embattled White House that for the eight years prior had been occupied by Richard Nixon and, after his resignation, Gerald Ford, Carter and first lady Rosalynn Carter treated the center of power not as a fortified bunker but as a kind of People’s Park. Members of the Woodstock generation were out of college and getting haircuts. The war was over, and with it the Selective Service draft.

“We thought we were celebrating victories that we had won,” says Nile Rodgers, producer and founder of funk band Chic, of the Carter presidency. “This is at about the height of the Black Power movement, the height of the women’s movement. The gay rights movement has come out.”

“Musicians are always looking for the truth, right? That’s kind of what they do as songwriters,” says director Wharton. In Carter, she continues, artists saw “a presidential candidate who was offering the truth and offering a real, authentic persona, and it wasn’t put on. It wasn’t an act.” Wharton won a Grammy Award for best music film in 2004 for her documentary feature “Sam Cooke: Legend” and has directed documentaries on Joan Baez and Phish.

Longtime friends and peers, Wharton and producer Farrell teamed up after the latter had been shocked by a conversation he’d had for a documentary he was making on the Allman Bros. He’d been speaking to former members of the Carter administration about the Allmans’ early fundraising support.

As Farrell was getting ready to leave, one of them asked, “Do you want to hear about Jimmy Carter and his friendship with Bob Dylan?” They gave Farrell and crew the lowdown, then asked if he knew about Nelson’s friendship with Carter. Farrell was transfixed. “I knew even before I got back to my hotel that I wanted to switch gears.” He called Wharton and they got to work.

When they were finished researching, they had a bounty of footage, including stellar recordings of an afternoon jazz concert on the White House lawn; a country-focused night of music inside the residence; a Paul Simon performance; and interviews with Carter and his son Chip, Dylan, Nelson, Garth Brooks, Trisha Yearwood, Jimmy Buffett, Roseanne Cash, former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and others.

“We were well-rounded as far as music at the White House,” recalled the president’s son, James “Chip” Carter, during a recent phone conversation. The second child of Jimmy and Rosalynn was 25 when his parents and his younger sister, Amy, moved into the White House.

During those years the younger Carter served as what he called “the unofficial liaison” between the music business and his father’s administration. He helped facilitate, for example, the Grateful Dead’s seminal 1978 concerts in front of the Egyptian pyramids.

The president’s namesake son recalls taking advantage of the perks. He could stay at the White House residence when need arose. Once there, he said, “You sit on the stairs while they were having a big ball in the other room and listen to some great music.” Or put on a suit and join in.

In the film, Chip recalls growing up in a household teeming with music, describing his father investing in what he called the most expensive stereo system in Plains, Ga. For audiophiles, what Chip lists when asked about it is instructive: “A McIntosh amplifier with AR1 speakers. We were in a pre-Civil War house, and he bought the best back then.” Referencing Henry Mancini’s hit “The Baby Elephant Walk,” Chip said, “The whole house would shake when the baby elephant walked. You couldn’t get it wrong, with the bass pounding.”

Carter, says Farrell, “was truly, truly, truly a fan” of music. “That was part of what resonated with us. He didn’t just like a song. He didn’t like an artist. He loves music, and it permeates his life.” Even at age 95, Carter still listens to music on headphones. He has remained friends with both Nelson and Dylan for more than 45 years, connections he’s kept since he was in office.

It’s hard to imagine a similar scenario with the Trump clan —unless Kanye West and Ted Nugent were down for a collaboration. The filmmakers, however, resisted the urge to compare Carter’s openness with the chainlink-fence-enclosed White House of 2020.

Asked why they didn’t mention the differences between the Trump and Carter White Houses, Farrell said they didn’t need to. Also, they wanted to convey a more positive message, which was “how (Carter) used music, how it’s impacted his life and how it impacts all of our lives. And this idealistic hope that music can bring people together. We got him to talk about it with the very fervent hope that this will happen again.”

During both his 1976 run and his presidency, Carter leaned into the suggestion that he was more connected to music than his political opponents. “It’s always good to see something come out of the South and have an unexpected achievement,” he quipped during opening remarks before a country performance.

The connection, however, was a double-edged sword, one made obvious when, during Carter’s 1976 run for president, Georgia prosecutors indicted one of Gregg Allman’s longtime associates on drug trafficking charges. Despite fear of reprisal, Allman testified against him.

A wiser politician might have cut ties with Allman for fear of blowback. Carter did the opposite. Wharton called the event “a perfect example of how Carter was willing to risk his entire political future on friendship.”

Chip Carter remembers that friendship in action: “Gregg and Cher came upstairs at the White House and had dinner with us. And then Gregg played (Harry) Truman’s piano and sang for like three hours after that —just with our family sitting there.”

Those performances were thrilling, but certainly haven’t become the stuff of legend. Asked whether he was the Carter offspring whose father had accused him of smoking pot at the White House, Chip pauses. He’s confirmed it in the past, and usually answers in vague terms.

“My guess is it’s true. If you’re talking about me and Willie, he was my friend,” he says. Asked to paint a picture, he replied with a sigh, “I’ve never talked about that before.” The 40th anniversary of that joint’s passing, in fact, is Sunday.

The date was Sept. 13, 1980. Carter was in the thick of his reelection campaign against Ronald Reagan. In Iran, 52 American hostages had endured more than a year of captivity.

Nelson was in the middle of a set at the White House. Recalls Chip, “In the break I said, ‘Let’s go upstairs.’ We just kept going up till we got to the roof, where we leaned against the flagpole at the top of the place and lit one up.’”

Adds Chip: “If you know Washington, the White House is the hub of the spokes —the way it was designed. Most of the avenues run into the White House. You could sit up and could see all the traffic coming right at you. It’s a nice place up there.”

—

Randall Roberts, Los Angeles Times, via McClatchy