By LZ Granderson, Los Angeles Times

After a yearlong search that took film producers around the globe, Paramount recently announced it has finally found its Bob Marley. Kingsley Ben-Adir, the British actor who portrayed Malcolm X in One Night in Miami, has been cast in the untitled biopic on the reggae star’s life.

Given some of the other names attached to the project — Reinaldo Marcus Green, the director of King Richard, the screenwriter Zach Baylin and the Marley family — I have no doubt about the quality of the film.

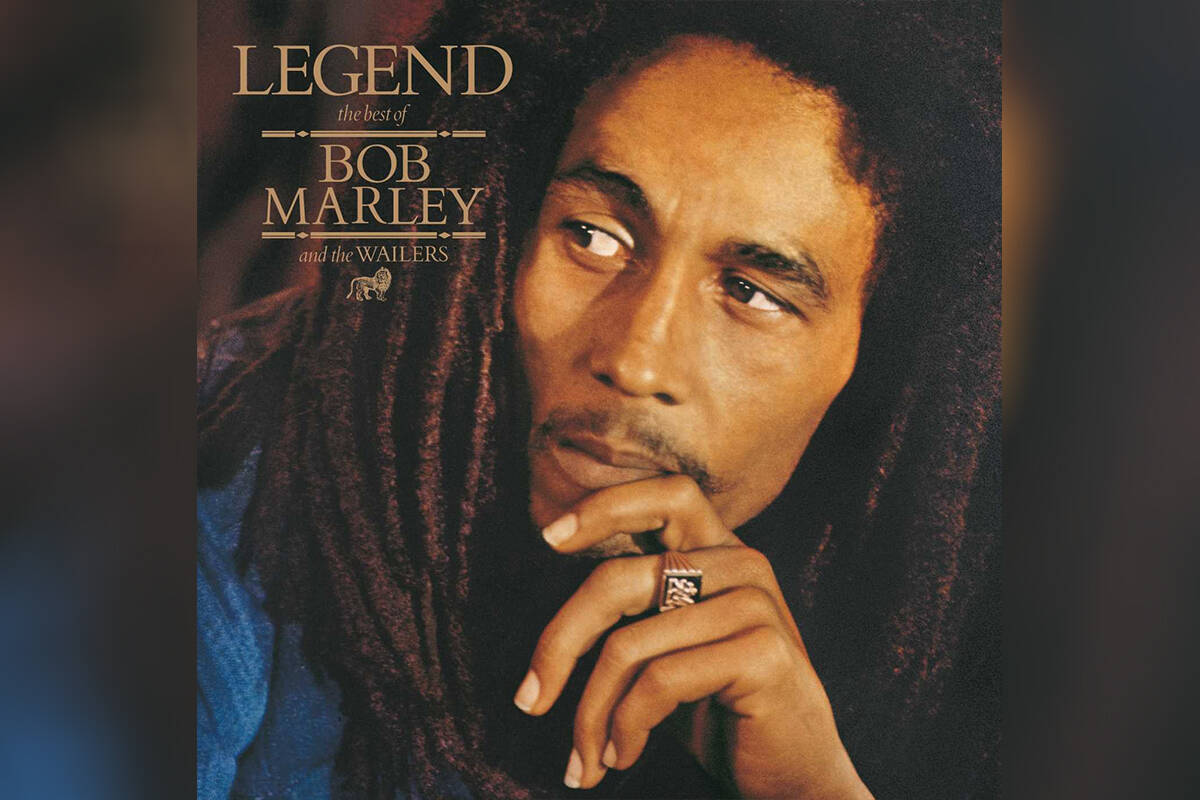

My question is which version of Bob Marley will audiences see: the revolutionary who struggled to sell records or the version that received a posthumous makeover that helped turn his greatest hits compilation into the second-longest charting album of all time. That’s right, at 717 weeks Legend: The Best of Bob Marley and the Wailers trails only Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon in terms of chart longevity.

Not a bad rebranding effort, considering that when Marley was alive, his highest selling album, Exodus, only sold 650,000 copies.

But when you read that the person in charge of putting together the setlist for Legend once said, “My vision of Bob from a marketing point of view was to sell him to the white world,” it becomes clear why the collection sounds oddly apolitical for a Black artist who was shot in a politically motivated assassination attempt and sang about Jamaicans being exploited by descendants of slave holders.

But hey, at least we know why “Crazy Baldheads” didn’t make the cut:

Didn’t my people before me Slave for this country? Now you look me with that scorn, Then you eat up all my corn

We gonna chase those crazy — Chase them crazy — Chase those crazy baldheads out of town!

I have a love/hate relationship with Legend. Other than Musical Youth’s “Pass the Dutchie” and the theme song to “Cops,” reggae was not a sound I heard much growing up. My world changed when I heard Legend. But while that version of Marley caught my ear, it was the politically charged lyrics of Marley’s “Burnin’ and Lootin” and “Simmer Down” — songs that sonically connected the African diaspora — that caught my heart and mind.

That’s not a slight against the songs of Legend. It is a fantastic listen.

But to make Marley more commercial in the 1980s, executives decided the album that has come to define an entire genre of music had to be curated by the very sensibilities much of Marley’s catalog criticized and challenged. Remember the era we’re talking about here: President Ronald Reagan’s war on drugs led to a surge in mass incarceration that disproportionately affected communities of colour. His wife, Nancy, pushed “Just Say No” instead of treatment. Later Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Gates went to Washington to tell the Senate Judiciary Committee that marijuana users “should be taken out and shot.” In other words, it wasn’t a good time to be promoting a pot-smoking Black man with a sharp tongue.

But times have changed.

My hope is that the biopic reflects that change and spends more time showing us how Marley came to be and less time highlighting the version shaped by executives after he died. According to the Village Voice, the producers were so worried that white listeners would reject what made Marley Marley that they initially chose not to use the word “reggae” in radio and television commercials for Legend.

This is akin to tweeting quotes from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. devoid of any mention of the racism he fought against (which happens a lot).

I get that producers aren’t in the business of making movies people don’t want to see. Leaning heavily into the “every little thing gonna be all right” Marley is the reason why Legend is currently sitting at No. 66 on the Billboard charts — nearly 38 years after its release and more than 40 years after Marley’s death from cancer.

A movie wrapped in the feel-good vibes that dominate the compilation has a much better chance of being a commercial success than a deep dive into the history of “Buffalo Soldier,” Marley’s tribute to the Black Civil War veterans who hoped that protecting white settlers moving west and fighting Native American tribes would lead to better treatment.

It didn’t.

“Buffalo Soldier” was a single from Confrontation, which was released two years after Marley’s death. Other titles on that album include “Blackman Redemption” and “Chant Down Babylon,” a call for Rastas to rise up anywhere Black people are oppressed. Yeah, I can see why they found “Buffalo Soldier” to be the safest choice to include in a yacht rock-ish collection.

Legend isn’t totally apolitical, it just isn’t as radical as the man whose music it’s celebrating. Be a shame if, after a year of searching for the perfect Marley, the film does the same thing.

Find the latest must-read stories from the cannabis world at canadianevergreen.com, your go-to source for news, trends, products and lifestyle inspiration from the cannabis community and beyond. You can also follow us on Facebook and Instagram and Twitter.